Powering the Future: Renewable Energy in Our Schools

1.0 Introduction

This year marked 16 years since the UN General Assembly adopted April 22 as International Mother Earth Day. This day is to “recognize the Earth and its ecosystems as humanity's common home and the need to protect her to enhance people’s livelihoods, counteract climate change, and stop the collapse of biodiversity” (UNEP, n.d.). The theme for the 2025 International Mother Earth Day was Our Power, Our Planet, a “call for everyone to unite around renewable energy so we can triple clean electricity by 2030.” (Earth Day, 2025).

In line with this theme, Lead For Ghana reflects on the role of renewable energy to improve education quality and student performance in pre-tertiary schools across Ghana. As part of our reflection, we incorporate views from the general public on electricity access during their pre-tertiary education and its impact on their education and learning.

2.0 Impact of electricity access to teaching and learning

Although the country boasts over 85% national electricity coverage, access to reliable electricity in schools remains a significant challenge in Ghana, especially in rural and underserved areas. As at 2018, the percentage of primary schools, junior high schools (JHS) and senior high schools (SHS) with access to electricity were 39%, 65% and 92% respectively (UIS, n.d.).

From the online survey, only 32.5% of respondents indicated consistent access to electricity. 58.0% of respondents reported experiencing frequent outages, which would negatively affect the learning environment. And 8.7% of the respondents reported having no electricity at all, a severe level of deprivation. This picture highlights the disparity in infrastructure across educational institutions and underscores the need for intervention.

Overall, the results (Figure 1) paint a picture of the need for investment in renewable energy solutions to bridge access gaps and ensure reliable electricity across all schools. Such measures could help level the educational playing field and significantly enhance learning outcomes across Ghana.

Figure 1: Electricity Access During Respondents' Pre-Tertiary School Days

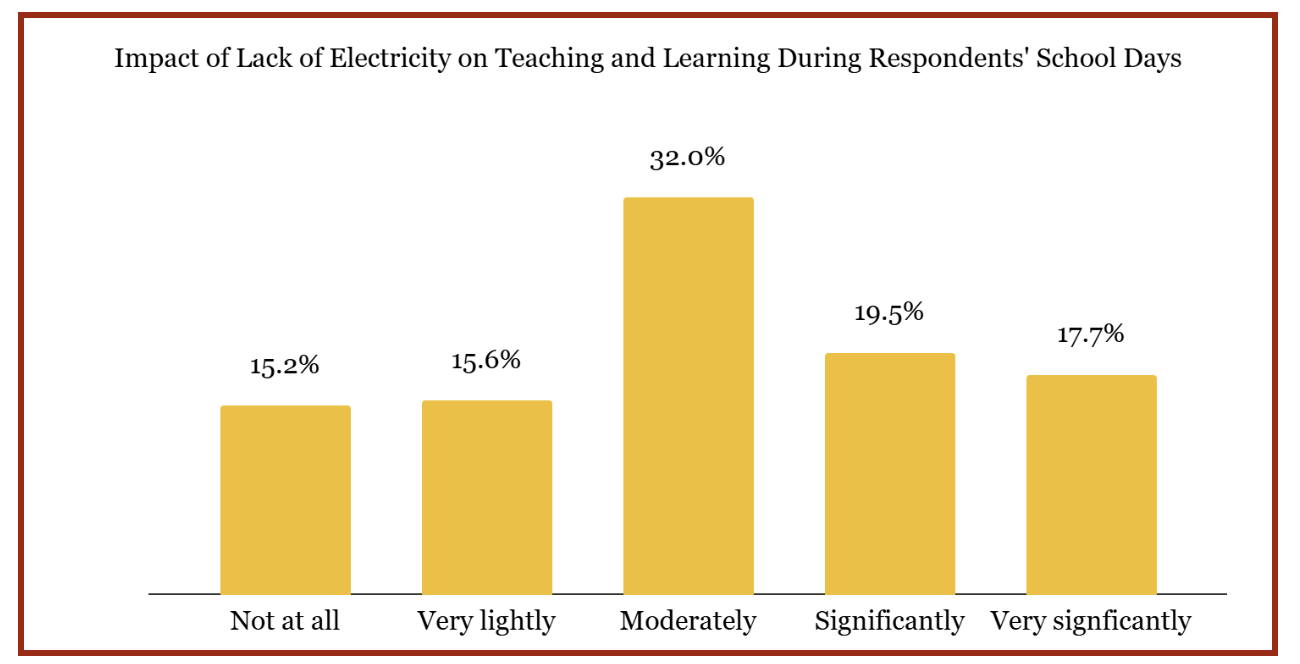

Access to electricity in schools impacts teaching and learning in multiple ways. 15.2% of respondents indicated that lack of electricity did not affect teaching and learning in their schools. Electricity access affected 12.5% of respondents very little and 32% of respondents moderated. Finally 37.2% of respondents indicated that lack of electricity affected teaching and learning significantly or very significantly.

Figure 2: Impact of Lack of Electricity on Teaching and Learning During Respondents' School Days

Literature provides examples of the ways in which school electricity access affects teaching and learning. First, school electrification contributes to improved student performance. Adamba (2017) shows that variations in district level student pass rates in BECE Mathematics and Science can be explained in part by school electrification. Pass rates in English and Mathematics increase in districts where a higher percentage of schools have functioning electricity lighting. These gains were more pronounced in deprived districts where schools had less resources to support teaching and learning. The presence of functioning electricity in schools meant teaching and learning could take place for longer hours. Students could spend more time in school to study and teachers could organize extra lessons in the evenings for students. Next, poor electricity access in schools hinders the use of educational digital tools and internet access in the classroom. For instance, Baako, Gidisu & Umar (2023) finds that the implementation of ICT in Education Policy has been hampered in schools without electricity access. By the end of the 2022/2023 academic year, only 15% of public primary schools and 13% of public JHS were equipped with functional ICT infrastructure, severely limiting the delivery of digital education (Boadi, 2024). Electricity access in schools and in the communities also facilitates the use of educational digital tools, which directly enhance learning outcomes (Boampong, Atta-Quayson & Gyamfi Ababio, 2024). Finally, electricity access in the school and community directly impacts teachers’ living conditions and therefore students’ learning. If teachers are less likely to like and work in communities with no or poor electricity access, it affects the quality of teaching and learning that happens in the schools (White, 2004). Overall, the impact of electricity access in schools and school communities on student learning outcomes and teacher satisfaction is clear.

3.0 Renewable energy in Ghana

Renewable energy presents itself as a suitable source of electricity for schools. When asked about their perceived benefits of renewable energy for schools and communities, many respondents recognized their role for better lighting for learning (83.3%), reliable power for computers and other educational devices that need electricity to function (79.2%), improved security at night (78.4%), reduced costs (59.7%) and a healthier environment (60.6%). However, while the majority of respondents (68.4%) had used or seen renewable energy sources at home or in a community setting, only 30.3% had used or seen renewable energy sources being used in a school. This suggests a gap in the use of renewable energy in schools to meet electricity needs.

Figure 3: Perceived Benefits of Renewable Energy for Schools and Communities

3.1 Snapshot of Ghana’s Energy Generation Sources

To identify how to address the electricity gaps in schools using renewable energy, it is important to understand Ghana’s current electricity situation and the feasible renewable sources for Ghana’s context. The current sources of energy supply in Ghana are crude oil and petroleum products (37.7%), biomass (29.8%), natural gas (26.4%), hydroelectric power (6%) and solar energy (0.1%) (Energy Commission, 2024). Renewable energy (i.e. biomass, hydroelectric power and solar energy) accounts for roughly 36% of these energy sources. For electricity generation, hydropower and other renewable energy sources account for 28.1% and 2.3% respectively, and thermal plants contribute 69.6% of Ghana’s electricity generation (Energy Commission, 2024). These electricity generation sources however are unable to meet Ghana’s growing energy demands due to population and economic growth, and increased urbanization and industrialization. The ability of the existing electricity generation plants to operate effectively all year round are also subject to a number of factors. For instance, the thermal power plants are dependent on the cost of fuel on the international market (Agyekum, 2020) and on the supply channels of the fuel to the country (Kuriakose et al., 2022; Dye, 2023). Hydro power plants are also dependent on water operational water levels. Low water levels affect the amount of water energy generated, high water levels affect machines, etc. It is therefore important for Ghana to heavily invest in other forms of electricity generation to meet the country’s needs. Renewable energy presents a good answer to meet the future electricity needs of the country whilst contributing to a clean future.

3.2 Feasible renewable energy options in Ghana

Researchers and policy makers have explored the feasibility of different renewable energy sources for Ghana. Although Ghana already has three hydropower plants (i.e. Akosombo, Kpong and Bui), there are still opportunities for the development of more hydropower energy plants, with a number sites identified as exploitable (Kumi, 2017; Kuriakose et al., 2022). Agyekum, Velkin and Hossain (2019) also found that northern Ghana is better suited for solar energy projects, while southern Ghana is best suited for wind energy. Kuriakose et al. (2022) also estimated that solar and wind energy has a resource potential of 1800 TWh and 240 TWh for Ghana. Plans for other renewable energy sources including wave and tidal energy, solid biomass, biofuels and waste-to-energy technologies have also been explored by the Ghana Energy Commission (2019). Finally, hybrid renewable energy sources such as the hydro-solar PV hybrid system currently under construction by the Bui Power Authority (BPA, n.d.) can also contribute to electricity generation in Ghana. And in communities that are not connected to the national grid due to economic and technical challenges, mini-grids based on all the above renewable energy sources can provide electricity access.

Despite the huge potential for various renewable energy sources in the country, there are a number of challenges that hinder their development. Huge financial investments are needed to construct these power plants. Poor policy implementation and discontinuity of renewable energy projects by future governments also affect the development of renewable energy power plants. Environmental and climate change risks also impact the development of renewable energy plants. For instance, the construction of these power plants can affect land and water bodies (Ghana Energy Commission, 2019). Overall, the potential for renewable energy is huge, however, the associated challenges for adoption need to be addressed in order for its full potential to be realized.

3.3 Renewable energy in schools

Ideally, school electrification should be part of efforts to increase electricity access for the country, which includes increasing renewable energy sources for the country. However, high costs of electricity from the national grid affects these efforts at the school level. For instance, in 2024, the Electricity Company of Ghana communicated that SHS across the country owe the company an estimated GHC 45 million (ECG, 2024). Renewable energy stand-alone or mini-grids present a great solution for providing electricity access in schools (Moner-Girona et al., 2025). These include solar photovoltaic (PV) systems and hybrid systems that combine solar with other renewable energy sources including agro-waste and biodiesel (Diemuodeke et al., 2024; Adaramola, 2017).

Before schools can adopt these renewable energy systems however, they need to conduct an energy needs assessment to understand their electricity requirements in order to choose the most appropriate renewable energy solution. To support costs associated with installation and maintenance, schools can seek financial and technical support from NGOs, donor agencies, and private organizations.

The main barriers to adopting renewable energy in schools are similar to barriers at the national level. These include financial constraints due high installation and maintenance costs, and the lack of technical expertise for installation and maintenance. Survey respondents also echoed these concerns including high costs (86.6%), maintenance concerns (77.5%), technical support (70.6%) and lack of awareness (32.5%) while 1.7% reported other barriers beyond the list provided in the survey.

Figure 4: Barriers to Renewable Energy Adoption in Schools and Communities: What Respondents Say

3.4 Recommendations for adopting renewable energy sources in schools

Both the government and private sector have roles to play in adopting renewable energy in schools. Some of their roles include:

Offering Financial Incentives: Provide subsidies, tax incentives, and low-interest financing to reduce the upfront costs for schools adopting renewables.

Encouraging Private Sector Engagement: Companies should be incentivized to invest in school electrification through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and public-private partnerships.

Community and school leaders can also get involved to increase renewable energy access in schools in the following ways:

Promoting Community Ownership and Accountability: Communities play a critical role in the success and sustainability of renewable energy projects in schools. When local stakeholders feel a sense of ownership, they are more likely to protect, maintain, and support these systems. Schools should actively involve traditional leaders, parent-teacher associations (PTAs), and community members in planning, decision-making, and oversight.

Forming Local Energy Committees: Establishing school-based energy committees made up of community representatives, teachers, alumni, and youth leaders ensures regular monitoring and accountability. These committees can be trained to handle basic maintenance, report faults, and coordinate with technical partners when needed.

Mobilizing Local Contributions: Encourage contributions- financial from the community to support system installation and upkeep. This strengthens community investment and reinforces the idea that everyone has a stake in the success of the school.

Leveraging Alumni Support: Schools and communities should maintain active alumni networks and engage past students in supporting electrification projects. Alumni can offer funding, expertise, or even help build partnerships with renewable energy providers. This call is important because it is evident in the research findings, where 88.3% indicated they are willing to support or advocate for renewable energy solutions in their schools and communities.

Finally, ongoing efforts to improve knowledge and skills in renewable energy at all levels of education, especially at the pre-tertiary levels, should be continued. A few of these efforts include:

Energy Efficiency and Conservation (EEC) materials for pre-tertiary schools: These materials include school club manuals for students to engage with renewable energy concepts and teacher toolkits on how teachers can incorporate renewable energy concepts in their lessons. The materials are developed by the Ministry of Education and the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) in association with Associates for Change (AfC) and Development Environergy Services Limited (DESL).

SHS Renewable Energy Challenge: This competition aims to raise awareness and educate on renewable energy and energy efficiency among students in SHS and Technical Institutions across the country (Energy Commission, n.d.). It is organized by the Ghana Education Service and the Energy Commission of Ghana.

Solar Hands-on training and International Network of Exchange (SHINE) project: The SHINE project is an EU-funded capacity building project that aims to “drive the green transition and enhance energy access in Africa” (SHINE, n.d.). The consortium partners for Ghana are Start-up SME Centres (SSC) - an organization that provides business formalization, development and entrepreneurship support to MSMEs across Ghana, and Suame Technical Institute - a public TVET school in Ghana.

4.0 Conclusion

As we reflect on the role of energy in shaping educational experiences, one truth becomes evident—access to reliable, clean energy is foundational to equitable learning, investing in clean energy is investing in our children’s future. The insights shared in this edition show that renewable energy is not only feasible but essential in bridging the gap between potential and performance in our schools.

This is our moment to reimagine education through the power of innovation and sustainability. With collective action from the government, private sector, and communities, we can light up every school in Ghana—not just with electricity, but with opportunity and hope. Reliable, sustainable electricity can transform classrooms, empower teachers, and unlock digital learning for all—regardless of geography or background.

The future of education is bright—let’s make sure it’s powered by clean, sustainable energy.

What’s your opinion on renewable energy in schools? Share your thoughts below.

5.0 References

Adaramola, M. S., Quansah, D. A., Agelin-Chaab, M., & Paul, S. S. (2017). Multipurpose renewable energy resources based hybrid energy system for remote community in northern Ghana. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 22, 161-170.

Agyekum, E. B. (2020). Energy poverty in energy rich Ghana: A SWOT analytical approach for the development of Ghana’s renewable energy. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 40, 100760.

Agyekum, E. B., Velkin, V. I., & Hossain, I. (2019, November). Comparative evaluation of the renewable energy scenario in Ghana. In IOP conference series: materials science and engineering (Vol. 643, No. 1, p. 012157). IOP Publishing.

Adamba, C. (2018). Effect of school electrification on learning outcomes: a subnational level analysis of students’ pass rate in English and mathematics in Ghana. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 17, 15-31.

Baako, I., Gidisu, P., & Umar, S. (2023). Access to Electricity in Ghanaian Basic Schools and ICT in Education Policy Rhetoric: Empirical Quantitative Analysis and Access Theory Approach. International Journal of Education and Management Engineering, 13(5), 23.

Boadi, C. G. (2024). Only 44% of primary schools, 63.9% of JHSs had access to electricity by 2020 — EduWatch. Retrieved April 15, 2025 from https://ghanaeducation.org/only-44-of-primary-schools-63-9-of-jhss-had-access-to-electricity-by-2020-eduwatch/

Boampong, T., Atta-Quayson, A., & Gyamfi Ababio, A. (2024). Effects of Electricity Access on Learning Outcomes in Ghana: The Role of Digital Technology. Available at SSRN 5126610.

Diemuodeke, O. E., Vera, D., Ojapah, M. M., Nwachukwu, C. O., Nwosu, H. U., Aikhuele, D. O., ... & Seidu Nuhu, B. (2024). Hybrid Solar PV–Agro-Waste-Driven Combined Heat and Power Energy System as Feasible Energy Source for Schools in Sub-Saharan Africa. Biomass, 4(4), 1200-1218.

Dye, B. J. (2023). When the means become the ends: Ghana’s ‘good governance’electricity reform overwhelmed by the politics of power crises. New Political Economy, 28(1), 91-111.

Earth Day (2025). Earth Day 2025. Retrieved April 23, 2025, from http://earthday.org/earth-day-2025

Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG). (2024). Senior High Schools owe us GHC45m – ECG MD. Retrieved April 24, 2025, from https://ecg.com.gh/index.php/fr/media-centre/news-events/senior-high-schools-owe-us-ghc45m-ecg-md

Energy Commission (2024). 2024 National Energy Statistical Bulletin. https://www.energycom.gov.gh/index.php/planning/energy-statistics?download=641:2024-energy-statistics

Energy Commission of Ghana. (2019). Ghana Renewable Energy Master Plan. http:// https://www.energycom.gov.gh/index.php/reports?download=29:ghana-renewable-energy-master-plan

Energy Commission (n.d.) Senior High Schools Renewable Energy Challenge. Retrieved April 24, 2025 from https://www.energycom.gov.gh/index.php/initiatives/ec-shs-renewable-energy-challenge

Kumi, E. N. (2017). The electricity situation in Ghana: Challenges and opportunities.

Kuriakose, J., Anderson, K., Darko, D., Obuobie, E., Larkin, A., & Addo, S. (2022). Implications of large hydro dams for decarbonising Ghana's energy consistent with Paris climate objectives. Energy for Sustainable Development, 71, 433-446.

Moner-Girona, M., Fahl, F., Kakoulaki, G., Kim, D. H., Maduako, I., Szabo, S., ... & Weiss, D. J. (2025). Empowering quality education through sustainable and equitable electricity access in African schools. Joule.

SHINE (n.d.). SHINE PROJECT. Retrieved April 25, 2025 from https://shine-project.com/about/

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (n.d.). Data Browser. Retrieved April 16, 2025, from https://databrowser.uis.unesco.org/

UNEP (n.d.) International Mother Earth Day 2025. Retrieved April 23, 2024, from https://www.unep.org/events/un-day/international-mother-earth-day-2025

White, H. (2004). Books, buildings, and learning outcomes: An impact evaluation of World Bank support to basic education in Ghana. (No Title).