From Graduation to the Job Market - The Tertiary Lens

1.0 Introduction

In the heart of Ghana’s bustling cities and quiet villages, a crisis exists —one that hides behind the proud smiles of graduation caps and the echoes of university anthems. Each year, thousands of young Ghanaians complete their tertiary education with dreams of gainful employment, only to be met by a harsh reality: the journey from school to work is anything but guaranteed. With caps tossed into the air in celebration, thousands of graduates each year face the sobering question: What now?

At Lead For Ghana, we believe youth employment is not just an economic issue—it’s a national imperative. That's why we launched an online survey to hear directly from those who matter most: the graduates themselves. Through the voices of 333 respondents, we explored critical questions—How long does it really take to land a job after graduation? Where are young people working today? What are the biggest barriers they face? And could entrepreneurship be the way forward? The findings are both eye-opening and urgent, and reveal the readiness of young people to be part of the solution—if given the chance.

2.0 Findings and discussion

The demographic data revealed that the majority of respondents 75.76% (250) completed tertiary education between 2021 and 2025, followed by 20.61% (68) who completed their education between 2011 and 2020, and 3.63% (12) who completed it prior to 2011.

2.1 Duration to first job after national service

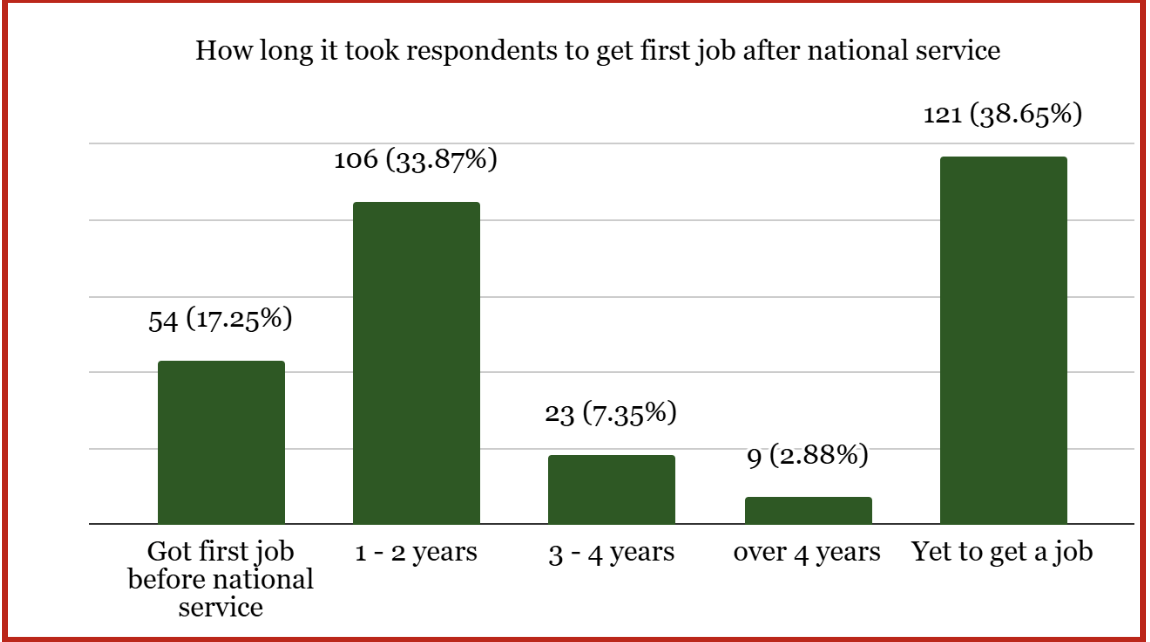

Among the 313 respondents who answered this question, 38.65% (121 individuals) are yet to secure their first job. A total of 33.87% (106 respondents) obtained their first job between one to two years after completing national service. Additionally, 7.35% (23 respondents) reported getting their first job between three to four years post-service, while 2.88% (9 respondents) were employed more than four years after national service. Notably, 17.25% (54 respondents) secured their first job before completing national service.

Corroborating these findings, earlier studies in Ghana have also highlighted extended unemployment durations among graduates. Yirenkyi et al. (2023) reported an average unemployment duration of two years among educated individuals, though those with tertiary education experienced a shorter average of seven months. Adinkra-Darko and Ahiakpor (2024) further emphasized that factors such as migration, strong social networks, and higher educational qualifications contribute to shortening unemployment duration. These local insights reinforce the notion that individual-level variables significantly influence employment timelines, and underscore the need for targeted support mechanisms to ease the transition from education to employment.

Drawing on international parallels, UK-based research indicates that graduate unemployment is not unique to Ghana. Pucci (2022) found that only 56% of UK graduates secured full-time employment within 15 months, while FE News (2023) noted that half of UK graduates took up to six months to find work. Although the timelines vary, these findings suggest a global challenge in graduate labor market absorption, further supporting the call for proactive employability strategies.

In the Ghanaian context, such strategies are increasingly relevant. As Emmanuel and Dzisi (2024) argue, delays in employment can adversely affect personal development and financial security. Practical interventions—such as promoting voluntary service, internships, and industry attachments—have been recommended by Adinkra-Darko and Ahiakpor (2024) as effective ways to bridge the skills gap and improve labor market outcomes. Ultimately, equipping graduates with practical experience and market-relevant skills remains a critical step in shortening unemployment durations and enhancing overall youth employment prospects in Ghana.

2.2 Job search challenges

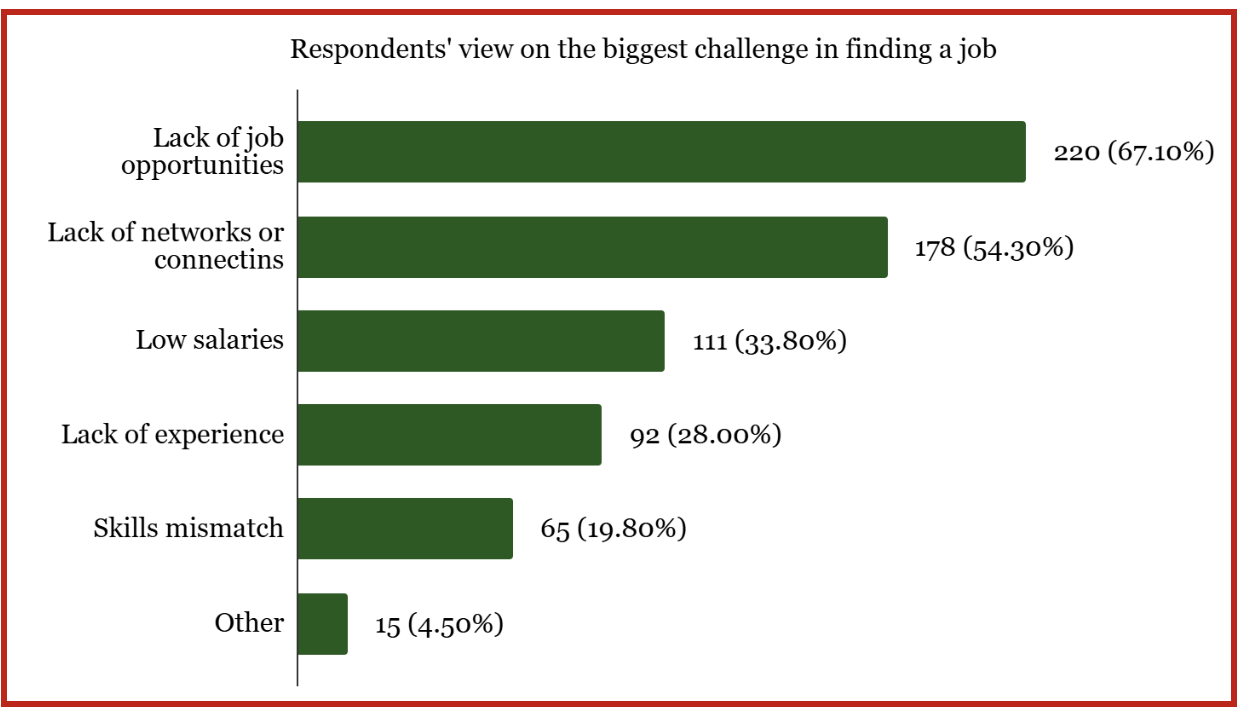

Respondents were also asked to identify the biggest challenges they faced in their search for jobs in Ghana. The results echo some of the challenges identified in literature. 326 individuals responded to this question. Lack of job opportunities emerged as the leading challenge, representing 65.10% of the responses (220 respondents). This was followed by 54.39% (178 respondents) who mentioned lack of networks and connections (commonly referred to in Ghana as ‘whom you know’). About 33.80% (111 respondents) cited low salaries as a major challenge. Lack of experience was mentioned by 19.80% (65 respondents), while 4.50% (15 respondents) pointed to other factors such as jobs not being advertised, the location of jobs, oversupply of graduates, and delays in job postings.

These results align with findings from literature. For instance, Baah-Boateng (2013) and Tornyezuku (2017) identified the lack of job opportunities as a main challenge in job search. Affum-Osei (2019) also found that job seekers in Ghana mostly use informal methods (especially particularly talking to friends and relatives) to find jobs. As such, individuals without the right network of friends and relatives struggle to find jobs. The quality of available jobs is also a challenge for job seekers including the youth. Adeniran et al. (2020) also found that employers offer jobs with low entry salaries to youth due to the lack of experience and skills among the youth. Finally, Bawakyillenuo et al. (2013) noted the mismatch between the skill sets desired by employers and industries and those possessed by graduates as a challenge in job search among the youth.

2.3 Youth employment through entrepreneurship

As part of the survey, we presented entrepreneurship as an avenue for youth to enter the job market. We asked respondents about their willingness to start their own business in the current climate of limited job opportunities. Among the 333 individuals who responded to this question,tThe majority of respondents (88%) indicated that they are ready and willing to start their own business and 8.1% of respondents stated that they have already started their own business. The results suggest high interest in entrepreneurship among the youth. Only 3.9% of respondents said they are not willing to consider entrepreneurship as an option.

Adams & Quagrainie (2018) identifies several reasons why young people consider entrepreneurship. Young people engage in entrepreneurship as a source of income - whether as their main source of income through self-employment or for extra income in addition to regular salaried jobs. Some young people also go into entrepreneurship as a result of their family background. These young people develop the skills and the interest in entrepreneurship as they engage in their family businesses. Finally, although few, some young people are encouraged to venture into entrepreneurship as they listen to motivational speeches from other entrepreneurs.

Regardless of their pathways however, young entrepreneurs face several challenges in their journey. Mensah, Fobih, & Adom (2019) identifies four themes of challenges for startup entrepreneurs. These are:

Inadequate finances, resources and other economic factors such as weak economies, high taxes and energy costs, high interest rates for loans, among others.

Lack of planning and key entrepreneurial knowledge and skills including management and technical training, organizational and risk management skills.

Lack of competitiveness in international markets, little to no technology innovation, and poor marketing strategies for market equity and customer loyalty

Inadequate legal and regulatory frameworks to support entrepreneurial businesses and negative social factors such as corruption, cultural attitudes and politicisation of government-sponsored loan schemes

Entrepreneurship education has the potential of solving some of these challenges young entrepreneurs face. For instance, capacity building as part of entrepreneurship education can build youth’s entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. The Government of Ghana also contributes to addressing challenges faced by young entrepreneurs. For instance, a number of policies and strategies have been launched to support youth entrepreneurship as a means of employment. These include the 2014 National Employment Policy, the 2015 Youth Employment Act (Act 887), and the 2022 - 2032 National Youth Policy. All these policies and strategies highlight the role of entrepreneurship in addressing unemployment among the youth. There are also a number of government agencies and programs to support the development of youth entrepreneurial businesses. For instance, the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Programme (NEIP) is also a flagship program of the government that provides integrated national support (e.g. business development services; startup incubators and funding) for start-ups and small businesses (NEIP, n.d.). The Ghana Enterprises Agency (GEA, n.d.) )also provides business development programs and integrated support services to micro, small and medium enterprises, many of which are entrepreneurial in nature. Finally, the Microfinance and Small Loans Centre (MASLOC, n.d.) provides financial assistance in the form of micro and small loans for start-ups and small businesses of Ghanaian entrepreneurs. However, more can be done by the government in creating supportive legal and regulatory frameworks that are favorable for building start-ups in the country. Overall, promoting entrepreneurship can help reduce youth unemployment, stimulate economic growth, and foster innovation, ultimately contributing to national development and social stability.

3.0 Final words

According to the World Bank (2020), Ghana faces a youth unemployment rate of 12% and an underemployment rate of over 50%, both of which surpass the regional averages for Sub-Saharan Africa. This will require that many Ghanaians, especially those with tertiary education, consider entrepreneurship as a viable career path. For individuals, embracing entrepreneurship can provide alternative sources of income, reduce dependency on limited formal jobs, and foster self-reliance.

Further review revealed that while entrepreneurship on its own reduces unemployment conditionally, its combination with innovation creates a strong and transformative economic force (Beynon et al., 2019). It was also noted that the effect of entrepreneurship on lowering unemployment is not immediate, typically taking at least five years to manifest (Padi & Musah, 2022). Additional insights indicate that entrepreneurial efforts in sectors such as construction, transportation and utilities, finance, and professional and business services have the most significant impact on reducing unemployment (Padi & Musah, 2022). Moreover, access to funding, credit, training, tax incentives, novel ideas, knowledge-driven activities, and self-sufficiency programs are essential elements in using entrepreneurship to combat unemployment (Padi & Musah, 2022).

This report doesn't just present statistics. It invites you into the experiences of a generation poised to drive Ghana’s future. Whether you’re a policymaker, educator, employer, or citizen, the insights shared here challenge all of us to rethink how we support young Ghanaians in their transition from school to work. The time to act is now. The future is waiting—and it wears a graduation gown.

4.0 References

4.0 References

Adams, S., & Quagrainie, F. A. (2018). Journey into Entrepreneurship: Access and Challenges of Ghanaian Youths. European Journal of Pediatric Dermatology, 28(4).

Adeniran, A., Ishaku, J., & Yusuf, A. (2020). Youth employment and labor market vulnerability in Ghana: Aggregate trends and determinants. West African youth challenges and opportunity pathways, 187-211.

Adinkra-Darko, E., & Ahiakpor, F. (2024). Unemployment Duration and Its Covariates: Evidence From Selected Regions in Ghana. SAGE Open, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241287606

Affum-Osei, E., Asante, E. A., Forkouh, S. K., Aboagye, M. O., & Antwi, C. O. (2019). Unemployment trends and labour market entry in Ghana: Job search methods perspective. Labor History, 60(6), 716-733.

Ampadu-Ameyaw R, Jumpah ET and Owusu-Arthur J, Boadu P and Fatunbi O. A (2020). A review of youth employment initiatives in Ghana: policy perspective. FARA Research Report 5 (5): PP41

Baah‐Boateng, W. (2013). Determinants of unemployment in Ghana. African Development Review, 25(4), 385-399.

Bawakyillenuo, S., Dankwa, S., & Agbelie, I. (2013). Tertiary Education and Industrial Development in Ghana. International Growth Centre (IGC) Working Paper.

Beynon, M. J., Jones, P., & Pickernell, D. (2019). The role of entrepreneurship, innovation, and urbanity-diversity on growth, unemployment, and income: US state-level evidence and an fsQCA elucidation. Journal of Business Research, 101, 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.074

Emmanuel, O., & Dzisi, S. (2024). The Effect of Graduate Unemployment on Career Development in Ghana. African Journal of Commercial Studies, 5(4), 203-216.

FE News Editor. (2023, September 27). SIX MONTHS: the average time it takes for a graduate to find a job in the current climate. FE News. https://www.fenews.co.uk/student-view/six-months-the-average-time-it-takes-for-a-graduate-to-find-a-job-in-the-current-climate/?

Ghana Enterprises Agency (GEA). (n.d.). About Us - Ghana Enterprises Agency. Retrieved May 23, 2025 from https://gea.gov.gh/about-us/

Microfinance and Small Loans Centre (MASLOC). (n.d.). Objectives - Microfinance and Small Loans Centre. Retrieved May 23, 2025 from https://www.masloc.gov.gh/objectives.html

Mensah, A. O., Fobih, N., & Adom, Y. A. (2019). Entrepreneurship development and new business start-ups: Challenges and prospects for Ghanaian entrepreneurs. African Research Review, 13(3), 27-41.

Okoro, J. P., Nassè, T. B., Ngmendoma, A. B., Carbonell Launois, N., & Nanema, M. (2022). Entrepreneurship education and youth unemployment challenges in Africa: Ghana in perspective. International Journal of management & entrepreneurship Research, 4(5), 213-231.

Padi, A., & Musah, A. (2022). Entrepreneurship as a potential solution to high unemployment: A systematic review of growing research and lessons for Ghana. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, 5(2), 26-41.

Pucci, C. (2022, May 11). How long does it take to find a job after graduation? UKCF. https://www.ukcareersfair.com/news/how-long-does-it-take-to-find-a-job-after-graduation?

National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program (NEIP). (n.d.) Home -National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program Retrieved May 23, 2025 from https://neip.gov.gh/

Tornyezuku, D. E. (2017). Causes and Effects of Unemployment among the Youth in the Ga West Municipality, Greater Accra Region (Doctoral dissertation, University of Ghana).

Yirenkyi, E. G., Debrah, G., Adanu, K., & Atitsogbui, E. (2023). Education, skills, and duration of unemployment in Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2258680

World Bank Group. (2020, September 29). Addressing Youth Unemployment in Ghana Needs Urgent Action, calls New World Bank Report. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/09/29/addressing-youth-unemployment-in-ghana-needs-urgent-action.