From Fields to Futures: How LFG Is helping to turn Child Labour into Classroom Dreams

1.0 Introduction

In 2024, Lead For Ghana embarked on a study to assess the impact of the Lead For Ghana model on 1) student learning, 2) parent’s mindset on child labour practices and their children’ future aspirations, and 3) attitudes and teaching practices of non-LFG teachers (i.e. GES teachers) in the Lead For Ghana partner schools in the Asunafo-South district in Ghana. At the time, Lead For Ghana had been operating in these communities for two years and we were interested in knowing how key aspects of our model directly impacted these broad outcomes. In honor of this year’s theme for the World Day Against Child Labour — “Progress is clear, but there's more to do: let’s speed up efforts!” — which acknowledges the work done around the world to address child labour and to push for more intentionality in eradicating child labour, we share some of our findings and learnings on the impact of the Lead For Ghana model on education and child labour practices in Asunafo South.

2.0 What constitutes child labour

DID YOU KNOW

Children under thirteen (13) years cannot be engaged in light work.

Children under fifteen (15) years cannot be engaged in any type of work except light work. This includes working as an apprentice.

Children under eighteen (18) years cannot engage in hazardous labour.

According to the Ghana’s Children’s Act, 1998 (Act 560), work that children engage in can be classified as either light work or child labour. Light work is work that is “not harmful to the health or development of the child and does not affect the child’s attendance at school or the capacity of the child to benefit from school work”. Light work includes work such as helping parents to sell at a shop or in cocoa-growing communities, helping parents with non-harmful work on the farm. Legally, a child has to be at least thirteen (13) years old before they can be engaged in light work. Note that light work is different from household chores such as cleaning and helping with cooking.

Unlike light work, child labour is “mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with children’s schooling” (Act 560). Some specific forms of child labour include hazardous labour (e.g. going to the sea, working with or around machines and chemicals, mining and quarrying, etc.) and worst forms of child labour (e.g. separation of children from their families, exposure to serious hazards and illnesses, leaving children to fend for themselves on the streets of large cities, etc.). Legally, the minimum age for children to work is fifteen (15) years old. However, children can only engage in hazardous labour when they are eighteen (18) and above.

3.0 Child labour statistics in Ghana

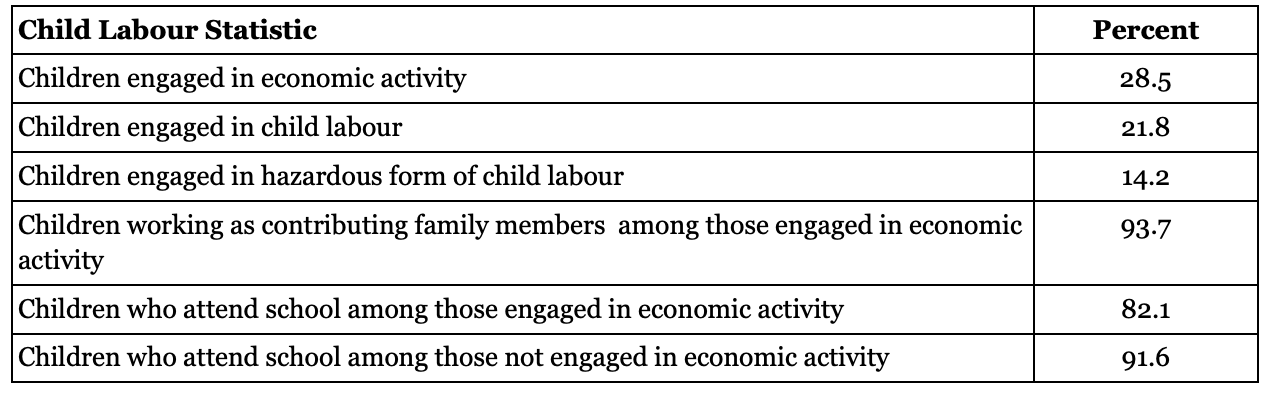

The most recent national report on child labour statistics are available in the 2014 Child Labour Report from the sixth round of the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS 6). The report shows that 28.5% of children in Ghana are engaged in economic activity, 21.8% are engaged in child labour, and 14.2% are engaged in hazardous form of child labour (GSS, 2014). Among children engaged in economic activities, 93.7% of them work as contributing family workers. In urban centers, more children work in non-agriculture economic activities, while children in rural areas engage in agricultural work. Finally, 82.1% of children engaged in economic activities still attend school. This aligns with studies that show that some children engage in economic activities for financial compensation that is used to support their educational costs (Hilson, 2010; Network Movement for Justice and Development, 2006).

Table 1: Child Labour Statistics

4.0 Efforts to eradicate child labour

4.1 The Lead For Ghana approach

The Lead For Ghana model for teaching and learning involves placing trained Fellows to serve as full-time teachers for a duration of two-years in these schools. In addition to regular classroom teaching, Fellows also engage in activities and projects that aim to improve educational outcomes of students and foster a positive and conducive learning environment with various members of the school community. Fellows actively participate in and lead school activities that aim to broaden students’ worldviews and enhance their academic experience. These include the establishment of student clubs such as literacy, science and maths and ICT clubs and the commemoration of significant international days such as the World Menstrual Hygiene Day, World Book Day, and Green Ghana Day. Fellows also engage with students, parents/guardians and communities outside regular teaching and learning activities. These engagements include home visits or phone calls to speak to parents about their children and address concerns in the home that might be affecting student attendance, motivation and learning; engagement with parents in school during Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) meetings to discuss school wide issues; and engagements with school and community members to embark on school and community-wide projects that addresses needs of the school or community. Overall, the activities and projects are tailored to the identified needs of the students and communities in which the Fellows find themselves. As such, in communities where child labour is identified as an issue, there is concerted effort by the Fellows across all their activities to help reduce the risk of child labour.

The 2024 evaluation of the Lead For Ghana program in Asunafo South involved a structured questionnaire administered to parents of students enrolled in the participating schools and a semi-structured interview with the headteachers of the participating schools. A total of 568 parents and six (06) headteachers participated in the data collection activities. The findings from the evaluation show that the Lead For Ghana approach has led to changes in child labour practices through two main route: first, through the reduction of teacher shortage, and second, through changes in the mindsets, attitudes and behaviours of parents, students and parents.

Reduction of teacher shortage

Headteachers reported that prior to the arrival of the Fellows, many of the schools had teacher shortages which led to teacher fatigue from overworking. The arrival of the LFG Fellows therefore addressed a major issue of teacher shortage in the participating schools. Students, who were previously not encouraged to attend school because they did not have teachers available to teach them, now had a reason to go to school. Parents were also more inclined to send their children to school now that they believed learning would happen in school with staffed teachers. Overall, the arrival of the Fellows led to increased student attendance as students and parents felt more assured that students will learn while in school.

Changes in teacher attitudes

Teacher attitudes also improved during the program. Headteachers noted that the presence of Lead For Ghana Fellows served as a source of motivation for many overstretched GES teachers. Inspired by the Fellows’ dedication and energy, GES teachers became more engaged in their roles and gradually began to adopt some of the effective teaching strategies modeled by the Fellows. Finally, similar to Fellows, GES teachers started engaging with parents outside of the school which have improved relationships between parents and GES teachers.

Changes in student mindsets and behaviours

Changes in student behavior were reported by both parents (Figure 1) and headteachers. Interviewed parents reported that their wards spend more time studying than they were used to, were eager to go school, and were completing their homework assignments regularly. Headteachers also noted that students’ motivation for learning had improved due to the Lead For Ghana Fellows. Overall, when students come to understand the value of education and know that teachers are in school and that learning is happening in school, students become more motivated to learn.

Figure 1: Parent responses on student motivation

Changes in parent mindsets and behaviours

The evaluation also found that parents’ value to education improved due the engagements that Fellows, with the support of the GES teachers, had with parents. Most parents interviewed have an improved understanding of the support they can give their children at home in order to improve the children’s academic performance (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Parent responses on changes in their own mindsets

Most parents also indicated that the visions they had of their children’s futures had changed. They had a clear vision for their children, and were contributing to the realization of their visions for their wards (Figure 3). Parents attributed these findings in part to their continuous engagement with Fellows.

Figure 3: Parent responses on changes in the visions they have for their children

4.2 Civil Society’s Role in the Fight Against Child Labour

In addition to Lead For Ghana’s efforts, several NGOs are actively engaged in addressing child labour across Ghana. A few of these organizations are described below.

In Kumasi, the Child Research for Action and Development Agency (CRADA) runs the “Smile Ghana Project,” which offers sensitization workshops, school feeding, and child rescue initiatives.

Challenging Heights, with a strong presence in both coastal and cocoa-farming areas, focuses on the rescue, recovery, and prevention of child trafficking, one of the worst forms of child labour. It also engages in policy advocacy and community education to reduce child trafficking in the communities they work in.

In Sunyani, Global Media Foundation (GloMeF) leads the “Rights4Cocoa” campaign, promoting anti-corruption and financial literacy to reduce child labour risks in cocoa communities.

Codesult Network operates in mining and cocoa-growing communities like Bibiani, training local observers to identify and prevent child labour cases at the grassroots level.

These organizations play complementary roles in advocacy, prevention, rescue, education, and systems strengthening to combat child labour nationwide.

4.3 Government and Global Partnerships in Ghana’s Child Labour Fight

All efforts to tackle child labour practices in the country will not be complete without input and support from the Government of Ghana. In 2023, the Government of Ghana, through the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relation (MELR) and together with other national agencies and development partners, developed the Ghana Accelerrated Action Plan Against Child Labour (2023 - 2027) which aims to accelerate actions to support national efforts to eliminate child labour in the country. Multiple international and funding partners including International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), International Labour Organization (ILO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank are working together on various initiatives to support the implementation of this action plan. The Action Plan builds on the gains made from the first National Plan of Action (NPA1) on the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour (2009-2015) and then the second National Plan of Action Phase II (NPA2) of the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour in Ghana (2017 – 2021).

5.0 Conclusion

The data and stories emerging from Asunafo South district reflect more than just progress—they demonstrate the transformative power of education when it is intentional, community-driven, and rooted in empathy. Through the strategic placement of trained Fellows, Lead For Ghana has not only bridged gaps in teacher supply but also catalyzed meaningful shifts in the mindsets and behaviors of students, teachers, and parents alike. Increased student motivation, improved parent involvement, and heightened school attendance are all evidence of a model that works—not in isolation, but in close partnership with local actors.

Yet, as this year’s World Day Against Child Labour reminds us, “Progress is clear, but there’s more to do.” While child labour has declined in the communities we serve, its complete eradication remains a national challenge—one that cannot be overcome by a single organization or policy alone. It demands coordinated, long-term investment in education, advocacy, and systemic change.

A key step to further amplify our impact is launching public awareness campaigns aimed at informing parents about the legal definitions of child labour—especially the prohibitions surrounding light work for children under 13 and hazardous work for those under 18. As parents become more aware and engaged in their children’s education, such initiatives can empower them to make choices that better support their children’s academic growth and long-term well-being.

We therefore issue a call to action—to our partners, stakeholders, and the broader community—to continue supporting Lead For Ghana and similar organizations committed to ending child labour across the country. Your support sustains vital interventions: from equipping classrooms and mentoring Fellows to organizing public awareness campaigns that educate parents on the hidden harms of child labour. Together, we can amplify the impact, extend the reach, and uphold every child’s right to learn, dream, and thrive.

Let us stand united in ensuring that no child is left in the fields when their future belongs in the classroom.

6.0 References

Child Research for Action and Development Agency (CRADA), (n.d). World day against Child labour, 2021. https://cradagroup.org/index.html

Challenging heights (n.d) https://challengingheights.org/

Ghana Accelerrated Action Plan Against Child Labour. National Plan of Action for Elimination of Child Labour) ( 2023 - 2027 ).

Ghana Statistical Services, 2014. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6) - Child Labour Report.

Ghana News Agency. 2023. Codesult Network.

https://gna.org.gh/2023/10/ngo-trains-community-observers-on-child-labour-eradication/

Global Media Foundation(GloMeF),(n.d). Child right survival and development. https://glomef.org/chiild-rights-survival-and-development/

Hilson, G., 2010. Child labour in African artisanal mining communities: Experiences from Northern Ghana. Development and Change, 41(3), pp.445-473.

International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), (n.d) Working together to tackle child labour in Ghana – new collaborative projects launched. (n.d.). ICI Cocoa Initiative. https://www.cocoainitiative.org/news/working-together-tackle-child-labour-ghana-new-collaborative-projects-launched

Network Movement for Justice and Development, 2006. ‘Report on the Situation of Child Miners in Sierra Leone: Case Study of Four Districts’. Freetown: Network Movement for Justice and Development.

The Children’s Act (1998, Act 560) of Ghana. Parliament House, Accra